- Books

- >

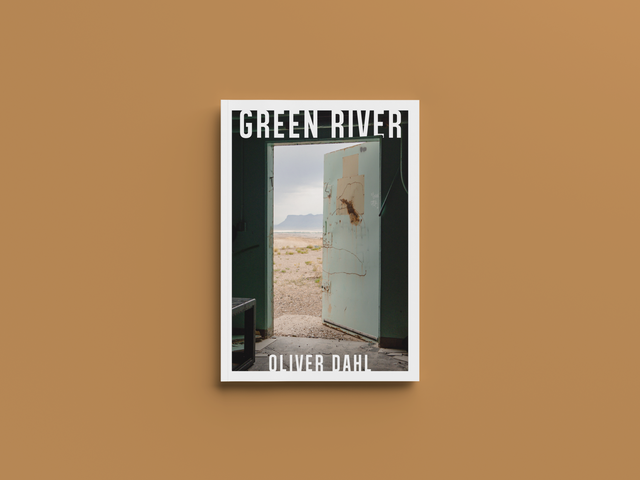

- GREEN RIVER

GREEN RIVER

Green River, Utah

pop. 847 (2020 Census)

"Waypoint to Wild"

GREEN RIVER is Oliver Dahl's third photo book in a series documenting small towns of the American West. (Following ARCO and WENDOVER.) The book features a combination of digital and analog photography, paired with stories and history from the desert town of Green River, Utah. Surrounded by stunning geology and crowded national parks, most visitors drive right past it—unaware of its rich history and small town charm. The remnants of cowboys, railroads, and Cold War-era missile testing sites are left behind.

This photo series is the result of 3 different trips—each in a different season—taken between 2021-2022. It studies the town's paradoxical role as both a remote waypoint and its liminality as a central landmark for "passing through."

Included in the book is a forward by James R. Swensen, associate professor of art history and the history of photography at Brigham Young University.

Details

88 pages, containing 66 full-color photos

Printed on 100 lb Satin Paper

6.69" x 9.61" (17 x 24.41 cm)

Collectible Images

Forward by James R. Swensen

Booms are impossible without movement and traffic. When the ancient Romans built colonies, they did so at the intersection of two primary roads: the cardo, which ran north and south and the decumanus, running east and west. Nearly perfectly aligned with the cardinal points, the Green River was (and is) the heart or cardo of the town. Its crossing, in all its different manifestations, is its decumanus. Centuries before Anglo Americans arrived, Fremont tribes left their remarkable pictographs on the rock walls of the area. Later other Native Americans—Utes, Shoshones, Diné/Navajo, and others—used the shallow waters of the river’s bend to cross east and west through the valley. They were followed by the Spanish, who incorporated this spot into their “trail” from Santa Fe to California and gave it their own name: “The Crossing of the Fathers.” In 1869 and again in 1871, John Wesley Powell and his intrepid crews floated the Green past the future townsite in their quest to plumb and understand the watery depths of the Colorado Plateau. On his first encounter, Jack Sumner, Powell’s right-hand man, noted that the region was “of little use to anyone; the upland is burned to death and on the river, there are a few cottonwood trees, but not large enough for any purpose but fuel.” [1] Frederick Dellenbaugh, who accompanied the one-armed explorer on his second expedition, noted that “the valley appeared as silent and deserted as it was desolate and barren.” [2]

The town’s first settler, Thomas Farrer, came a few years later seeking to get “as far away from civilization as possible.” [3] Not sharing Major Powell’s dire assessment or Farrer’s desire for dislocation, Mormon colonizers arrived by 1880, buoyed up by their belief that they could make any desert bloom. Although early residents begrudgingly admitted that the “Green River was hard to control,” they saw promise. They built canals to use its waters to plant crops and establish farms. One of these hardy colonizers, Francis Lyman, envisioned that the newly named town could support “homes and farms for one hundred men.” [4] Soon Green River City boasted “a post office, store, ferry, and three families.” By the end of the century, there were 222 residents and it was reported that after several attempts the settlement efforts in “reclaiming the desert…were more or less successful.” [5]

Eventually, the ferry across the Green River was replaced by a bridge and then by the rails. The Denver & Rio Grande Western railroad arrived in 1882 and with it came the contradictions of growth as gun fights accompanied opportunity. [6] The “elegant” Palmer House/hotel featured “fine grounds, planted trees and ornamental shrubbery.” Its presence, a contemporary argued, “gave quite an impetus to outside investors and Green River enjoyed a small boom in land values and commercial importance.” [7] Other opportunities, however, proved to be longer lasting. Early residents quickly observed that the mild climate and dry soil was ideal for harvesting melons and other crops and in 1898 it was reported that “all kinds of fruits and vegetables” were “growing in great profusion.” [8] Early on, the promise that the region would become “a most important fruit vale” was supported by the railroad, which brought its crops to market. [9] In the devastating drought of 1931, for example, Green River melons were sold at a premium in Boston and New York City. [10] Although no longer transported by rail, the fruit industry continues to be an important and visible part of the town’s identity. Nowhere is the more visible than in the annual festival, “Melon Days,” that takes place each fall with its panoply of watermelon-themed forms.

The town’s identity was also shaped by the river, its namesake. For the remainder of the nineteenth century, few followed Powell and his crews down the Green and Colorado Rivers. This short list included the ill-fated Brown-Stanton Expedition, which began their perilous trip from Green River on May 15, 1889. That would change in the following century when more and more ventured past the town into “the cliff-bound stream” toward the confluence of the Colorado River and the enticing perils of Cataract Canyon. [11] Local resident and one of the patron saints of the river, Bert Loper, made his first trip down the Green in 1907. He was followed by Nathan Galloway and Julius Stone in 1909, Ellsworth and Emory Kolb in 1911, and others who used Green River as the jumping off point for “800 miles of wilderness.” [12]

In the twentieth century, Green River not only became a river town but was increasingly connected to the outside. Paved roads and telephone lines linked the formerly isolated town with the rest of the world. This was particularly true following World War II, when the federal government became interested in Green River. Looking to meet the Atomic Age’s demand for radioactive fuels, the region experienced a uranium boom in the 1950s. [13] For the next decade this boom brought money and jobs to the area but ended abruptly. The Cold War also brought a missle testing center to the area. From 1964 to 1975 the Green River Launch Complex experienced nearly 250 ignitions in the efforts to keep U.S. advance ballistics at the ready. Never before had global interests and needs come so close to home.

The greatest impact to Green River, however, would come in individual automobiles. After the war, Americans began to look beyond the places where they grew up. [14] Moreover, greater access to cars facilitated a deeply rooted desire to travel. Across the country, motels provided respite from the long, open road. Motels attempted to attract travelers with plucky names and bold, neon signs. Billboards also dotted both ends of town, spreading the word of upcoming facilities in hopes of luring customers. With its proximity to Arches and Canyonlands national parks as well as its equidistance from nearly everywhere else, Green River benefited from these newfound freedoms and the desire to travel by providing motels and diners for weary and hungry travelers. Travelers could stay at the Robbers Roost, the Castle Country Motel, or the Sleepy Hollow Motel, which boasted cheap rates.

At first glance, it seemed as if the construction of Interstate 70 would bring in more tourists and more income, by providing greater access to the area’s scenic wonders, like Goblin Valley or Dead Horse Point. Rather, by bypassing the heart of town, it made it easier to reach other, more distant locales like Moab, Grand Junction, or the Wasatch Front, and effectively ended the earlier boom. [15]

In the decades that followed, Green River’s tourism industry suffered a sharp decline. The town would be seen more for its decay than as a destination.

Although not well known, Green River has a rich connection to photography, which provides an important window into the ups and downs of its past. The first photographer to work in Green River was E.O. Beaman who came in 1871 with the Powell Survey. From August 29 to September 2, Beaman explored the region and made several “views,” or photographs, in the company of Powell, Clem Powell (the major’s nephew), and the sturdy oresman Jack Hillers. Hillers, who would later become the survey’s chief photographer, did not see the visual potential in the region noting that “its God’s country, for man don’t want it.” [16] Eighteen years later, F.A. Nims, the photographer for the Brown-Stanton expedition, and the local postmaster, recorded their disembarkation from under the railroad bridge. [17] At this point it seems as if there was reason for hopeful optimism. This would soon change and three of the men in his photograph would perish downstream.

At some point the famed western photographer William Henry Jackson traveled through the region by wagon and photographed the jagged Book Cliffs to the northwest. Later, on March 23, 1900, the Utah photographer George E. Anderson made a visit to Green River, which did not have a studio photographer of its own. Initially he commented that it was “a dry and forbidden looking place.” [18] Yet, as he “canvased” the town he started receiving orders from residents for photographs, enlargements, and “prospects for other work.”

He photographed the Palmer House, the children of F.P. Fuller, and Miss Lulu Curtis’s class of thirty-six students. Before the train arrived to bring him home to Springville, he also able made several “views” of the bridge and other sites. The Kolb brothers stopped by Green River in the fall of 1911 in their quest to retrace Powell’s expedition down the Green and Colorado Rivers. To publicize their efforts, they brought along a camera as well as a film camera. During their stopover they took pictures, restocked their photographic supplies, and used a local darkroom. [19]

For the next few decades, it seems, the photography of Green River was fairly quiet. This would change in April 2021 when the photographer Oliver Dahl began documenting the town and its environs. Dahl’s series was made during the pandemic, which helps explain his desire to get out to someplace new. To see the world anew was a familiar byproduct of this strange and often constricting time. For nearly a year, the photographer returned to Green River Country to capture it in different seasons and in different light. After similar investigations of Wendover, Utah/Nevada, and Arco, Idaho, Dahl has learned how to capture the essence of small western towns. To the outsider, these towns may appear similar. Yet, through his careful, photographic prowling, Dahl has learned that each site has unique characteristics in detail, color, and light.

Dahl’s series reflects an astute study of landscape photography from the past. His personal study of Green River and other western towns harkens back to the great western surveys of the West in the nineteenth century. It also aligns with other trends including the New Topographic aesthetic, which has dominated the photography of the West since the 1970s. [20] This style presented a different view of the world than that of photographers like Ansel Adams, who projected a vison of western landscapes that was picturesque and pristine. Instead, photographers like Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, and Henry Wessel, found their subject matter in subdivisions, industrial parks, and the detritus of the West. While their vision was closer to the realities of the West, it was not void of visual interest; it embraced irony and celebrated contradictions. In favoring color, Dahl also works within the legacy of Stephen Shore, Joel Sternfeld, and others who made color an essential element of their work especially while on the road.

Through his photo-documentation, Dahl insightfully captured evidence of Green River’s ups and downs. A cheery Christmas tree, for example, standing proudly and defiantly on 200 West, reveals the town’s resilience and hope. A wasp-colored high school marching band with volunteers among its ranks reveal its youth and spirit of cooperation. Green River, after all, may have repeatedly “boomed,” but it never busted. Yet, it is impossible to ignore the decay of the past, which might be the most important theme of this series. It is visible in the form of dilapidated motels that once welcomed visitors. He captured parking lots filled with tumble weeds and room doors left ajar. A shot inside one room shows outdated motel furniture with colors and patterns that were popular in the past but now muted by dust and neglect. The most important example of decay may be Dahl’s photograph of an erstwhile bank located on Main Street. Banks are good indicators of a community’s prosperity but better barometers of economic hardship. With windows boarded up, it is possible to see a bank that failed and a T-shirt store that later occupied the building, which couldn’t make it either. Yet, what Dahl demonstrates in these examples is that there is beauty in decay and value in the contemplation of ruin.

The sense of decay is amplified by the silence in Dahl’s series. This is a largely uninhabited place. Dahl explained that part of this was the result of working during COVID and a “post-pandemic world.” The timing, he believes, may explain the solitude and isolation that permeates these photographs. Clearly, he added, these attributes added to the artistry of the work but “there really just were no people out and about in most of the places.” [21]

As with every corner of the United States, cars and trucks are a central feature of modern life. In Dahl’s photographs of Green River, there are many newer automobiles, but it is the old, battered, and yet beautifully colorful cars and trucks that are of central importance. Take, for instance, a turquoise truck in the distance or the rusted Pontiac muscle car with its green frame and cracked dashboard. It seems as if the photographer could not resist the gravity of the picturesque, vintage automobile. The best image in the text may be Dahl’s photograph of the inside of an ancient Oldsmobile Continental, a fitting name for a car in this state and space. The photograph features a remarkable range of yellows from straw-colored seats to the ochre-tinted remains of a plant, which strangely doesn’t seem out of place. As evinced in this example, Dahl has a keen sense of color and its subtleties, which requires a patient and astute eye. This has always been true of this region. Although he was initially blinded by desolation, Frederick Dellenbaugh, who joined the Powell Survey as its artist, noted the importance of color on his first visit in 1871. Shortly after walking upstream from the future townsite at dusk, he recorded:

The effects of light and color all around us playing over the mountains and valley gave the surroundings a weird interest. The day was ending. Long shadows stole across the strange topography while the lights on the variegated buttes became kaleidoscopic. … Gradually the lights faded, the shadows faded, then both began to merge till a soft grey-blue dropped over all blending into the sky everywhere except west where the burnish of sunset remained… Silence and the night were one as in the countless years that had carved the dim buttes from the rocks of the world primeval when man was to. Beautiful is the wilderness at all times, at all times lovely, but under the spell of the twilight it seems to enfold one in a tender embrace, pushing back the sordid, the commonplace, and obliterating those magnified nothings that form the weary burden of civilized man. [22]

In this remarkable passage, Dellenbaugh exemplifies that color often needs to be discovered and that light can reveal deeper meanings. [23] Working purposefully in the changing light of the day and season, Dahl, likewise, captured a range of hues from subtle to bold. This is certainly true of the kaleidoscopic colors found in photograph of a former gas station that was recently converted into a taco stand with its deeply saturated reds and yellows. With his keen understanding of light and color, Dahl was better able to capture and convey a sense of place.

A sense of place is also fostered by Dahl’s views, which incorporate the surrounding landscape.

While the first artists who visited this area bemoaned the “broken mountains, sandy plains, beds of rivulets and square sandstone,” Dahl embraces them. [24] One early resident even complained that “the desert began at our back door.” [25] Dahl seems to intuit this through the open doors and windows that frame important local features including Little Elliott’s Mesa with its striated forms. These formations, in turn, provide a framework for his photographs and ground them to this place. Furthermore, while the proximity to desert may have been a determent to previous generations, by the mid twentieth century the nearness of desert forms and wilderness was increasingly seen as a virtue.

Another important feature of Dahl’s work in Green River is the incorporation of telephone poles and wires. In a way they are yet another physical reminder as to how a formerly isolated community is connected to an outside world. Visually, however, they have a more important purpose. While these details were once the bane of landscape photographers, they take on an important role in this series. As the work of the Rephotographic Survey Project and the photographers associated with New Topographics attest, it is nearly impossible to avoid electrical and telephone lines in the photography of the West. Rather than try to ignore them as Ansel Adams would have done, Dahl embraces them. [26] Indeed, they act as important formal elements that energetically break up the picture plane in a manner similar to the artist Charles Demuth who incorporated what he called “ray lines” or “lines of force” in his Precisionist paintings. They also link the series together, streaming from one image to another.

There is one last photograph that may quietly be as important as any in the series. It features a new hotel, a Holiday Inn Express & Suites, located on the westside of town; its boxy form broken up by a series of telephone and electric wires that parallel the geological bands in the distance. Even from afar, this structure provides a sharp contrast to the ruins Dahls documented in town. It also provides a window into the recent changes that are affecting Green River.

Indeed, the booms which have defined the town’s history and carefully recorded in Dahl’s series are not over. The latest boom, that of a renewed and expanded tourism, is bound to shape Green River and its environment as profoundly as any from the past. The same post-pandemic impulses that brought Dahl to its streets are propelling thousands of tourists to venture out to places like central Utah. The unprecedented lines of cars leading into Arches National Park are emblematic of this new change that will affect this region. As Moab and other hotspots in the West become overrun by tourists, people are starting to look elsewhere. Green River is a logical next stop. Already many have moved to Green River and many more will follow. As they do, they inevitably will clean up, fix, or update many of the picturesque elements that Dahl so beautifully captured in his work. Ruin, for better or worse, will be harder to find. And so, in the years to come, Dahl’s series will be a reminder of the subtle beauty of this place and a historical account of what Green River once was.

Press, 2015) and In a Rugged Land: Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, and the Three Mormon Towns Collaboration, 1953–1954 (University of Utah Press, 2018).

|

[1] Jack C. Sumner, Diary Entry (July 13, 1869) in The Exploration of the Colorado River in 1869-1872, eds. William Culp Darrah, Ralph V., Chamberlin, Charles Kelly (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2009), 114.

[2] Frederick S. Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage: The Story of John Wesley Powell and the Charting of the Grand Canyon (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2017), 94-95. [3] Edward A. Geary, A History of Emery County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1996), 71. [4] Ibid., 73. [5] W.H. Lever, History of Sanpete and Emery Counties, Utah (Salt Lake City: Tribune Job Printing, 1898), 596; Geary, 191. [6] Geary, 109-110. See also Robert G. Athearn, The Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad (Lincoln: Bison Books, 1962), 122. [7] Lever, 644. [8] Ibid. [9] Ibid. [10] Geary, 279. [11] Clyde Eddy, Down the World’s Most Dangerous River (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1929), 4. [12] Eddy, 11. [13] See Frederick H. Swanson, Wonders of Sand and Stone: A History of Utah’s National Parks and Monuments (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2020), 154-155. [14] Lewis Atherton, Main Street on the Middle Border (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1954), 237. [15] See this author’s “The Old Toponymy and New Topography of Zion: Utah, Photography, and Daniel George’s Series “God to Go West,” Utah Historical Quarterly 90, no. 3 (Summer 2022): 237-239. [16] Don D. Fowler, ed. Cleaving an Unknown World: The Powell Expeditions and the Scientific Exploration of the Colorado Plateau (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2012), 68. [17] Robert Brewster Stanton, Down the Colorado, ed. Dwight L. Smith (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1965), 36-39. [18] Rell G. Francis, The Utah Photographs of George Edward Anderson (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979), 17. [19] See Ellsworth L. Kolb, Through the Grand Canyon from Wyoming to Mexico (New York: Macmillan, 1914), 124-127. [20] For more on New Topographics see William Jenkins, New Topographics: Photographs of Man-Altered Landscape (Rochester: International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, 1975); Britt Salvesen, New Topographics: Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicolas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, Henry Wessel, Jr. (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2009). [21] Oliver Dahl, email correspondence with author, January 12, 2023. [22] Dellenbaugh, 101. [23] In this regard Dahl is like Dorothea Lange who while working in Utah in 1953 used light to characterize each of the southern Utah towns she was photographing. For more see this author’s In a Rugged Land: Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, and the Three Mormon Towns Collaboration,1953-1954 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2018). [24] Robert Shlaer, Richard Kern’s Far West Sketches (Salt Lake City: Boxelder Books, 2021), 281. [25] Geary, 194. [26] See Ansel Adams, Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1983), 94-95; Andrea G. Stillman, Looking at Ansel Adams: The Photographs and the Man (Boston: Little Brown, 2012), 131- 132. |